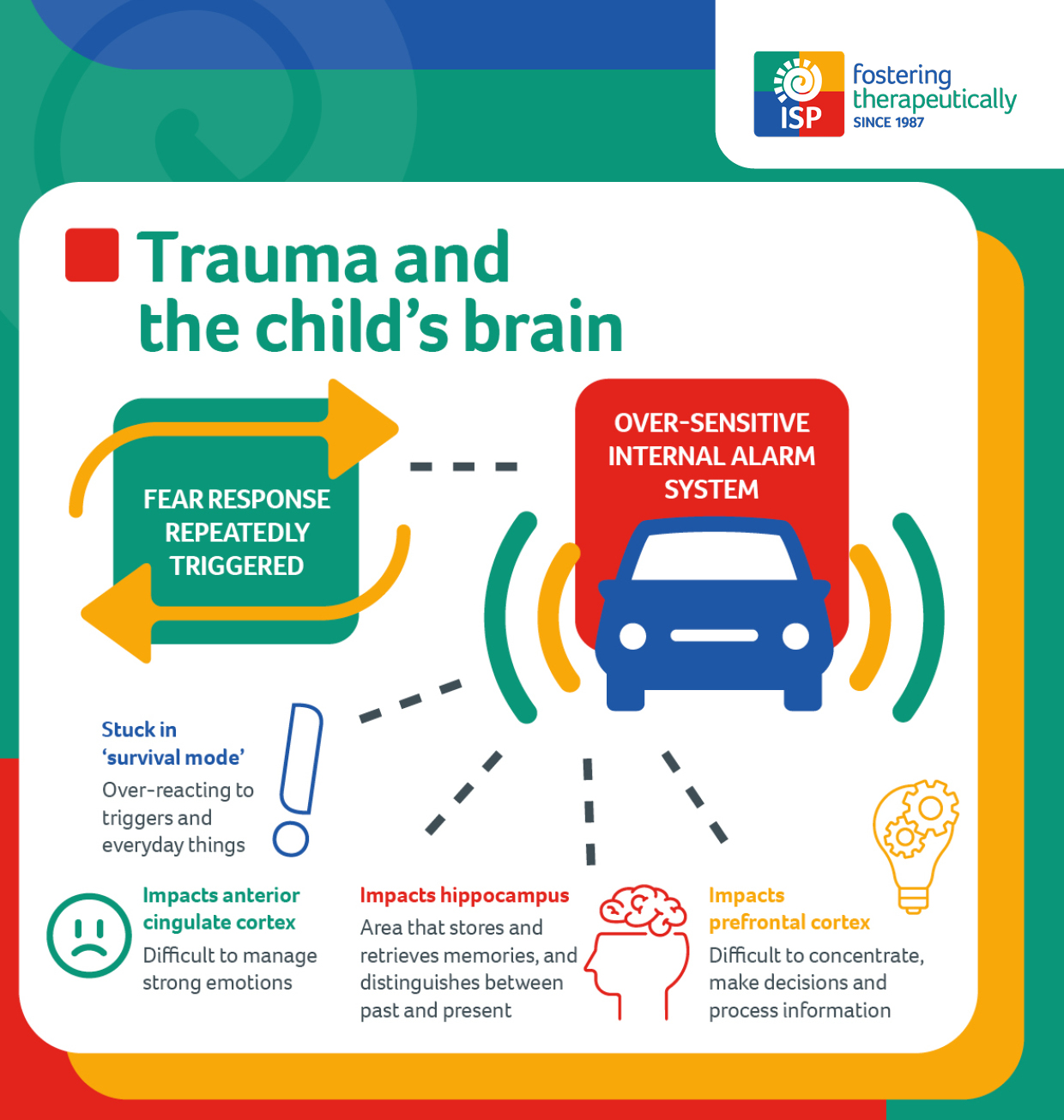

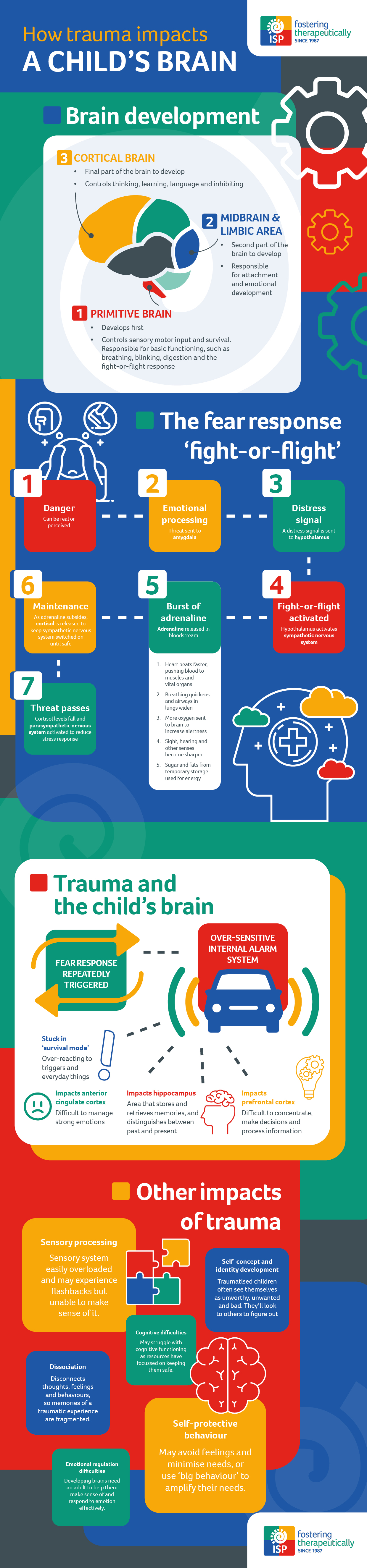

This can leave the child feeling unsafe, fearful, irritated, and extremely sensitive to small everyday things such as a slightly raised voice or a classroom move. They may feel numb or not in contact with the here and now, they may redouble efforts to keep themselves feeling safe by anticipating and meeting the perceived needs of important people around them.

As well as causing elevated stress responses, trauma can also change the way the prefrontal cortex (aka ‘the thinking centre’) functions. This can make it more difficult to concentrate, make decisions and process new information. Similarly, brains which have adapted to danger may function differently in the anterior cingulate cortex (aka ‘the emotional regulation centre’), so managing strong emotions can be challenging.

Studies have also shown that trauma can impact the hippocampus - a vital part of the brain that stores and retrieves memories, as well as distinguishes between past and present events. Therefore, traumatic memories can replay in a child’s mind and seem like the threat is current, even if the memory happened in the past and the child is safer now. Triggers for these memories could be anything from a sound, smell, environment or situation to an image, movement, facial expression or touch.